Government fleet operations rely on a large network of third-party vendors, which involve everything from GPS providers to fuel card systems and maintenance software. These partnerships support critical functions across the fleet, but each one also opens the door to potential cyber threats and expands the attack surface.

According to a recent study, 15% of data breaches involve third parties within the supply chain, putting organizations at risk through no direct fault of their own. This is particularly relevant for public-sector fleet managers, whose data often includes sensitive location information and infrastructure access points.

Managing this risk goes beyond procurement. It takes ongoing oversight, and the outcome depends on how well agencies manage third-party vulnerabilities – especially as vendor security plays a bigger role in operational risk.

Why Vendor Security Has Become a Core Risk Factor

Each vendor relationship typically introduces a potential point of failure, not just in service reliability but also in how vendors access, store, or transmit data.

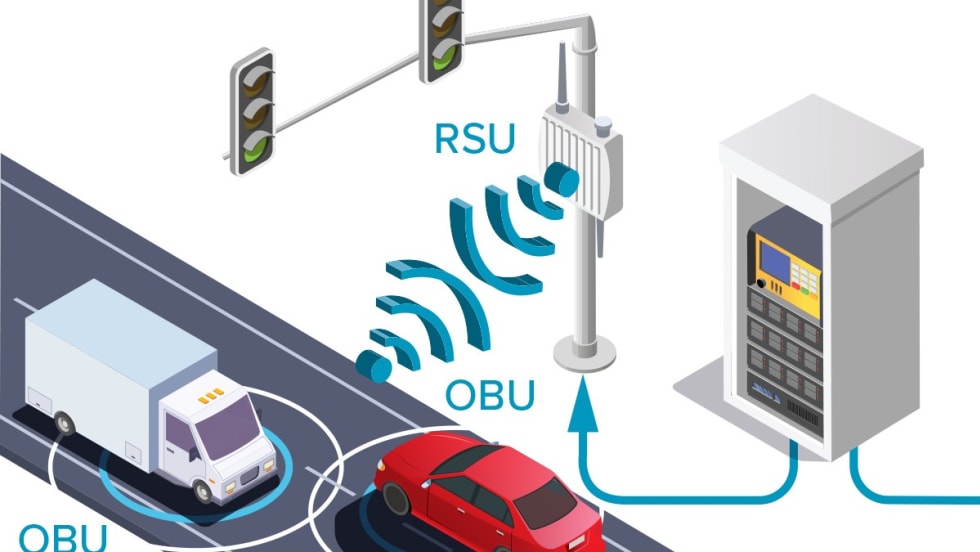

As fleet systems grow more interconnected, there’s an increased risk of sensitive operational data being exposed and/or misused.

According to Prevalent's 2024 Third-Party Risk Management Study, 61% of organizations experienced a third-party data breach or security incident in the past year, a 49% increase over the previous year's findings. This surge underscores the growing concern among organizations, with 74% citing data breaches or security incidents as their top concern regarding third-party relationships. For government fleets, such risks warrant heightened attention.

Understanding the Nature of Third-Party Risk in Fleet Operations

Third-party risk can take many forms, including data interception during transmission, weak access controls on the vendor’s side, outdated or unpatched software, and non-compliance with state or federal cybersecurity requirements.

As the General Services Administration (GSA) emphasizes in its Cybersecurity Supply Chain Risk Management (C-SCRM) Acquisition Guide, agencies must look beyond the surface of vendor relationships and account for embedded risk throughout the technology lifecycle. This approach involves both evaluating the primary vendor and assessing the third-party tools, subcontractors, and upstream suppliers they rely on to deliver products and services.

In fleet contexts, this could mean a GPS tracking vendor that outsources cloud storage to a third-party provider overseas. Or a vehicle diagnostics tool that updates remotely, without clear documentation on who can access the software pipeline.

Key Red Flags in Vendor Relationships

A lack of visibility is often the first warning sign. Vendors that are slow to provide documentation about their data handling practices or won’t disclose their own subcontractor relationships should trigger further scrutiny.

Other red flags include:

Limited or vague language in Service Level Agreements (SLAs) about security responsibilities

No clear incident response plan shared with customers

Absence of certifications or third-party audits

Reliance on outdated encryption standards or lack of multi-factor authentication (MFA)

Again, for government fleets specifically, this could manifest as an unsecured API between a fuel tracking system and an internal financial ledger or poor DNS configurations that allow attackers to intercept or reroute traffic, leaving transaction data exposed in transit or at rest.

Due Diligence Questions Before Signing Any Contract

A standardized vetting process is one of the most effective tools for reducing third-party risk. Government agencies should consider asking vendors the following before entering into any agreement:

What specific data do you collect and where is it stored?

Who has access to that data, including subcontractors?

Do you encrypt data in transit and at rest?

What cybersecurity frameworks or standards do you follow (e.g., NIST, ISO 27001)?

Have you undergone any third-party security audits in the past 12 months?

Can you provide documentation of your incident response process?

How quickly do you report breaches or anomalies?

These questions help clarify who is ultimately accountable when a breach happens and whether the vendor is prepared to mitigate threats in real time.

Embedding Security into Vendor Selection and Management

Cybersecurity needs to be part of procurement from the start, not something addressed reactively. That includes requiring vendors to submit security architecture documentation, demonstrating encryption practices, and maintaining a defined patching cadence.

Additionally, agencies should:

Include cybersecurity obligations in all contracts.

Conduct ongoing performance monitoring, not just annual reviews.

Create offboarding protocols that revoke access immediately when a contract ends.

Establish shared incident response plans across departments and vendors.

The stakes are high. If a key system goes down, even for a few hours, the ripple effects can hit everything from grocery store shelves to hospital supply chains. This was clear during the COVID-19 pandemic, when shortages of essential goods were tied to breakdowns across supply and logistics networks, as noted by the FTC.

Securing vendor relationships helps prevent those disruptions from starting in the first place.

What Happens When a Vendor Gets Compromised?

Despite best efforts, breaches still happen. When a third-party vendor is compromised, government fleet operators need to respond fast and in coordination with internal and external stakeholders in the following ways:

Disconnect the Affected Vendor Systems

The first step typically involves disabling any integrations, data flows, or access points connected to the affected vendor to prevent further exposure. This helps contain the incident and limits the potential for continued access.

Activate the Incident Response Plan

Once the threat is contained, the agency’s incident response plan should be activated. Ideally, this plan has already been shared with key departments and vendor contacts so everyone understands their role and escalation procedures.

Notify Internal Stakeholders

Relevant internal teams (including IT, compliance, legal, and public affairs) should be brought in right away. These groups play critical roles in containment, assessment, and external communication.

Conduct a Forensic Investigation

A forensic investigation can help clarify what data was accessed, which systems may have been exposed, and whether any malicious code or persistence mechanisms were introduced during the breach.

Revoke Access and Review Permissions

It’s essential to review and, where necessary, revoke any credentials granted to the compromised vendor. This includes API keys, remote access credentials, or role-based permissions that may still be active in connected systems or cloud environments.

Prepare for Public Communication

If the incident has external impact or media visibility, public communication may be necessary. Transparency (backed by documented mitigation steps) can help decrease reputational damage and maintain stakeholder trust.

Taking Full Ownership (Even Without Direct Control)

Managing a fleet often means relying on technology the agency doesn’t fully control. When that technology is integrated into a tight ecosystem, a single weak link can disrupt everything around it.

That’s why the most resilient government fleets approach third-party risk with the same rigor they’d apply to their own internal systems. After all, anticipating risks keeps agencies in control of their operations while protecting the people who depend on them.